AP Syllabus focus:

‘Even when more women work, they may still face wage gaps and unequal employment opportunities.’

Persistent gender inequality in wages and employment opportunities reflects structural barriers that limit women’s economic advancement even as overall development and labor-force participation levels rise.

Persistent Inequality in Wages and Employment Opportunities

Although global development has expanded educational access and increased women’s labor-force participation, gender disparities in pay and employment remain embedded in many economic systems. This subsubtopic focuses on how unequal outcomes persist even when women enter the workforce in greater numbers. Understanding these patterns is central to AP Human Geography’s analysis of development, labor markets, and social change.

Why Wage and Employment Inequality Persists

In many societies, women’s growing economic participation does not automatically translate into equal earnings or access to high-paying jobs. Several interacting forces—cultural, structural, and spatial—shape these ongoing disparities.

Social norms and gendered expectations continue to influence hiring decisions, workplace behavior, and assumptions about women’s roles in households.

Economic structures often reward industries dominated by men while undervaluing feminized sectors such as caregiving or service work.

Institutional constraints, including limited access to leadership tracks, unequal parental leave, or discriminatory practices, affect long-term income and opportunities.

Spatial patterns of development create region-specific gaps, with core countries typically offering more protections than semiperipheral or peripheral economies.

Understanding the Wage Gap

The gender wage gap measures the average difference in earnings between women and men.

Gender Wage Gap: The difference between men’s and women’s average earnings, expressed as a percentage of men’s earnings.

This gap reflects both direct discrimination and indirect factors, such as occupational segregation or unequal access to advancement.

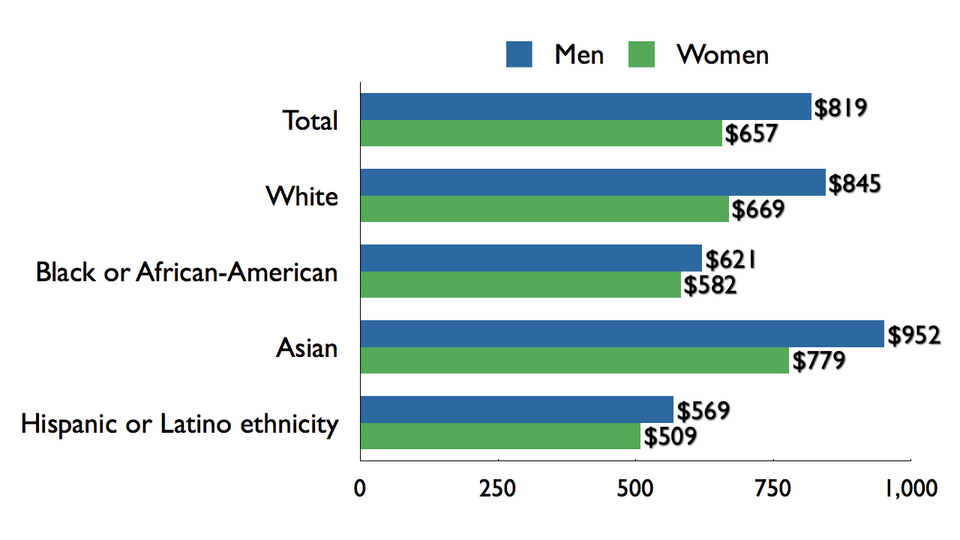

This bar chart shows median weekly earnings in the United States in 2009, comparing women’s and men’s pay across major racial and ethnic groups. It illustrates that women in every group earn less than men, underscoring how gender wage gaps persist even when women work full-time. The chart includes intersectional detail beyond the syllabus focus, reinforcing how wage inequality is layered and structural. Source.

Wage inequality does not simply reflect individual choices; it emerges from labor-market structures shaped by development level, sectoral composition, and historical norms.

Occupational Segregation

Occupational segregation plays a major role in persistent inequality. It occurs when men and women are concentrated in different types of jobs.

Occupational Segregation: The division of workers into different occupations based on demographic characteristics such as gender.

This pattern creates durable wage inequalities because sectors dominated by women often receive lower pay, fewer benefits, and less job security.

In industrial and postindustrial economies, segregation can appear in several forms:

Horizontal segregation, where women cluster in certain industries (education, health services, clerical work).

Vertical segregation, where women hold fewer senior or managerial positions even in sectors where they are the majority.

Informal-sector concentration, especially in developing regions, where women work in low-paid, unregulated jobs without legal protections.

Barriers to Employment Opportunities

Beyond wages, women frequently lack equal access to job training, promotions, and leadership roles. These disparities function as both economic and spatial phenomena.

Structural Barriers

Human capital gaps emerge when women receive fewer opportunities for advanced education or technical training.

Discriminatory recruitment and promotion systems limit women’s upward mobility within organizations.

Leadership stereotypes restrict women’s representation in corporate, political, and technological sectors.

These barriers accumulate over time, producing long-term impacts on lifetime earnings.

Household and Care Responsibilities

Societies often expect women to shoulder disproportionate care work, creating constraints on labor participation.

Limited childcare availability can force women into part-time work or informal employment.

Career interruptions during childbirth or caregiving reduce opportunities for promotion.

Unequal expectations reinforce employer biases that women are “less committed” to careers.

These dynamics interact with national development levels; wealthier states may offer social policies that lessen the burden, while poorer states may lack such supports.

The Role of Development in Inequality Patterns

Economic development influences the scale and form of inequality but does not eliminate it.

In Core Countries

Stronger legal protections reduce overt discrimination, yet pay gaps endure in high-tech, finance, and corporate leadership.

Service-sector growth creates many jobs, but high-wage positions remain male-dominated.

Women’s representation rises in education and health but remains low in engineering, energy, and executive roles.

In Semiperiphery and Periphery Countries

Women are more likely to work in low-paying export-processing zones or informal markets.

Barriers to education and training heighten inequality.

Limited labor protections increase vulnerability to exploitation and wage suppression.

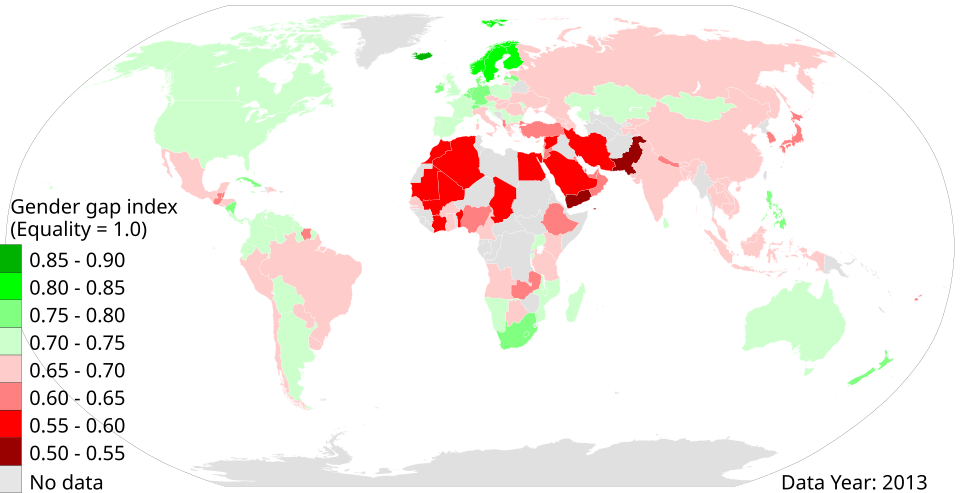

This choropleth world map displays the Gender Gap Index, summarizing levels of gender inequality across countries. Shading differences help illustrate where gaps in economic participation and other dimensions remain largest. The index includes factors beyond wages and employment, offering broader context for persistent inequality. Source.

These global patterns reflect how industrialization, trade networks, and labor-market restructuring shape gendered opportunities.

Impacts of Persistent Inequality

The consequences extend beyond individual earnings and influence broader development dynamics.

Reduced household income limits access to education, health care, and financial security.

Lower GDP potential emerges when half the population cannot fully contribute to high-productivity sectors.

Spatial development disparities intensify as regions with higher inequality experience slower economic transformation.

Intergenerational effects reinforce cycles of poverty and limited opportunity.

Pathways Toward Greater Equity

While inequality persists, strategies can help narrow wage and opportunity gaps.

Expanding access to education and vocational training prepares women for higher-paying sectors.

Strengthening employment protections, including equal pay laws and parental leave, reduces structural disadvantage.

Supporting childcare infrastructure enables women to pursue full-time work.

Encouraging leadership development and mentorship programs increases representation in senior roles.

Addressing cultural norms through public campaigns and education shifts expectations about gender and work.

This photograph shows Afghan women sewing blankets in a Kabul textile factory, representing women’s employment in industrial labor within a developing-country context. It demonstrates how women participate in manufacturing while often facing distinct economic constraints. The focus is on workplace conditions that relate to persistent inequality in employment opportunities. Source.

These approaches highlight how societal, institutional, and economic interventions are necessary to reduce persistent inequality in wages and employment opportunities.

FAQ

Unpaid care work reduces the amount of time women can spend in paid employment, which limits their access to full-time roles, promotions, and skill development.

These constraints accumulate across the life course. Women may re-enter the workforce later, with less experience than male counterparts, lowering their lifetime earnings.

Some employers also assume women will take more career breaks, which can influence hiring decisions and reinforce persistent wage gaps.

Leadership pathways often reward uninterrupted career progression, which can disadvantage women who take breaks for caregiving.

Recruitment and promotion systems may also rely on informal networks dominated by men.

In addition, stereotypes about leadership qualities can influence how women’s skills are perceived, making it harder for them to be selected for senior roles.

Women in many countries disproportionately work in informal sectors because these jobs offer flexibility but limited protections.

Informal work typically lacks:

Minimum wage rules

Job security

Legal recognition

Access to benefits

This leaves women more vulnerable to exploitation, suppresses earnings, and restricts their ability to move into formal, higher-paid roles.

Yes. Cultural norms strongly shape labour-market participation by influencing which jobs are considered acceptable.

In some regions, women may be discouraged from working in mixed-gender environments or travelling far from home, narrowing their employment choices.

These restrictions can push women into local, low-wage sectors such as domestic work, small-scale retail, or home-based production.

Technological advancement can widen or reduce inequality depending on access to training.

If women have limited opportunities to learn digital or technical skills, they may be excluded from higher-paying jobs in emerging sectors.

Conversely, remote work technologies can increase flexibility and support greater labour-force participation, though only when access and digital literacy are equitable.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which occupational segregation contributes to persistent gender inequality in wages.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

1 mark: Identifies occupational segregation (e.g., concentration of women and men in different jobs).

1 mark: States that women-dominated jobs tend to be lower paid or undervalued.

1 mark: Explains the link to persistent inequality (e.g., structural pay gaps remain because women are overrepresented in low-wage sectors).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

(4–6 marks)

Using examples, analyse how differences in economic development between core and periphery countries shape women’s employment opportunities and contribute to long-term gender inequality.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

1 mark: Identifies variation in development levels between core and periphery regions.

1 mark: Describes how women in core countries may have greater legal protections or access to higher-skilled jobs.

1 mark: Describes how women in periphery countries may be concentrated in low-paid manufacturing, informal work, or export-processing zones.

1 mark: Explains how these differing opportunities reinforce long-term gender inequality.

1 mark: Uses at least one relevant example (country or sector).

1 mark: Offers clear analysis connecting development level to structural labour-market inequality.